This post was written by Sara Phenix, a BYU Humanities Center faculty fellow.

The unlikely first sign that something was wrong with my vision was a broken ankle. On the second day of a two-week research trip to Paris in December 2023, I missed the last step of a staircase on the Ile de la Cité and rolled my ankle, fracturing my lateral malleolus in the process. It was a near-identical repeat of a stumble I had had the night before when I misjudged the drop of an uneven Parisian sidewalk and tripped over the curb. The second time, however, the urban terrain was less forgiving. I spent the remainder of my time in the city in a red-soled medical boot (a Lou-boot-in, if you will), limping my way across Paris with all of the grace of Victor Hugo’s hunchback.

It took a few more months for me to realize that I was going blind. Almost imperceptibly at first, and then all at once, I lost vision in my left eye due to a rapidly developing cataract. Over the course of four months, my vision deteriorated from 20/15 to 20/80; it then only took six weeks for me to go from 20/80 to hand movement vision, meaning that I could discern the agitation of a hand in front of my face but not the number of fingers, much less the top line of the Snellen chart.

A self-portrait taken in September 2024 at the Moran Eye Center reveals the milky nebula of a posterior subcapsular cataract in my left eye, the result of prolonged corticosteriod use. Steroid eye drops were my only recourse in tamping down chronic, painful ocular inflammations related to my autoimmune disease. Enter the pharmakon: the medicine that mitigated my excruciating eye pain is also what eventually robbed me of my vision.

Sara Phenix. Self-portrait at the Moran Eye Center. 2024. My eternal gratitude goes to Drs. Marissa Larochelle and Akbar Shakoor, both of the Moran Eye Center, for restoring the vision in my left eye and for their expert, compassionate care.

Sara Phenix. Self-portrait at the Moran Eye Center. 2024. My eternal gratitude goes to Drs. Marissa Larochelle and Akbar Shakoor, both of the Moran Eye Center, for restoring the vision in my left eye and for their expert, compassionate care.

I returned to Paris in the spring of 2025 to co-direct a Study Abroad program. The most moving thing I stumbled across during this subsequent trip was an exhibit at the Musée de l’Orangerie called “Dans le Flou, une autre vision de l’art de 1945 à nos jours” (“Out of Focus: Another Vision of Art from 1945 to Present Day”). The collection of works explored the aesthetics of blurriness in a variety of media from the twentieth- and twenty-first centuries. The inspiration for the exhibit was the anchor attraction of the Orangerie—Claude Monet’s Les Nymphéas (Water Lillies) (1914-26), a series of expansive canvases adhered to the walls of two adjacent oval-shaped rooms “that form the symbol of infinity.” The elliptical continuity of the paintings, illuminated by the natural light that enters the room, creates an ethereal, immersive experience for those who come to admire Monet’s work.

Sophie Crépy. Les Nymphéas gallery. Musée de l’Orangerie.

Sophie Crépy. Les Nymphéas gallery. Musée de l’Orangerie.

Claude Monet. Les Nymphéas (Reflets verts). 1914-26.

Claude Monet. Les Nymphéas (Reflets verts). 1914-26.

The Nymphéas cycle was the primary focus of the last part of Monet’s career. But this series is also remarkable because it demonstrates the blurring effects of cataracts on Monet’s vision in his later years. What catalyzed the artist’s late-career innovations is precisely what caused me to stumble (and my ankle to splinter) that December in Paris. Critics and medical experts alike have theorized that the abstraction and murkiness of Monet’s Nymphéas reflect in part the increasing opacity of his optical lenses. Vincent Dulom’s Hommage à Monet (2024) suggests as much as it captures the near-total dissolution of form into a vaguely circular diffusion of blue.

Vincent Dulom. Hommage à Monet. 2024.

Vincent Dulom. Hommage à Monet. 2024.

The debilitating disorientation of vision loss rushed back to me that May day at the Orangerie. Albert Londe’s X-ray image of a right foot triggered the memory. The distinct outline of the subject’s phalanges, enveloped by the hazy silhouette of a fleshy foot, reminded me of my own souvenir X-ray from December 2023, and the blurriness that led to my broken ankle.

Albert Londe. Radiographie d’un pied chaussé. 1897 or 1898.

Albert Londe. Radiographie d’un pied chaussé. 1897 or 1898.

American Hospital of Paris. Vanitas: X-ray of my right ankle. 2023.

American Hospital of Paris. Vanitas: X-ray of my right ankle. 2023.

Hans Hartung’s painting T1982-H31 recalls both the color motif of Monet’s Nymphéas and the blurry outlines of the X-rays. Labeled an undesirable by the Nazi regime because of his “degenerate” Cubist style, Hartung left his native Germany for Paris in the 1930s, ultimately joining the French Foreign Legion after the start of World War II. He was arrested several times over the course of the conflict, once by the collaborationist French police who, upon learning that Hartung was a painter, detained him for months in a red-walled cell “in an attempt to disturb his vision” and thereby rob him of his ability to paint. Hartung survived the war, but not before losing his right leg to amputation after a battlefield injury on the Alsatian front. He spent the rest of his career exploring the limits and possibilities of blurriness in visual abstraction, limping across Paris, just as I did, on a pair of crutches.

Hans Hartung. T1982-H31. 1982.

Hans Hartung. T1982-H31. 1982.

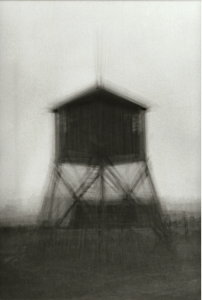

The spectral vibration of Krzysztof Pruszkowski’s 15 Miradors, Madjanek, Poland evokes the haunting nature of its central subject—a guard tower on the grounds of the Madjanek concentration camp. The blurry image is a result of Pruszkowski’s “photosynthesis” technique, a process in which the artist creates otherworldly compositions through the superposition of images. In a 2009 interview, Pruszkowski describes how his method of photographic layering evokes the ineffable by multiplying the semiotic possibilities of his subjects:

I take photos of things that have never existed, do not exist, and will never exist. It is not the result of my imagination or someone else’s imagination […] I create on photographic paper a virtual diagram resulting from the interplay of forces and energies existing between the forms and myself during the Photosynthesis experience.

Pruszkowski’s work at once draws us in and destabilizes us, refusing to settle into defined lines or easy resolution; it compels us into a dynamic negotiation of form and meaning. Terrifyingly, 15 Miradors reverberates with death and life, both as a historical symbol of the Nazi genocide and as a shadowy figure of the virulent anti-Semitism that still plagues the world today. In its intrinsic blurriness, Pruszkowski’s 15 Miradors suggests that trauma exceeds the grasp of defined form: it cannot be depicted; it can only be evoked. In the face of such brutality, all that is solid does indeed melt into air.

Krzysztof Pruszkowski. 15 Miradors, Madjanek, Poland. 1992.

Krzysztof Pruszkowski. 15 Miradors, Madjanek, Poland. 1992.

Pruszkowski’s pictorial monument of violence and grief conjured a personal memory of loss for me that day in the Orangerie. September 26 marked the two-year anniversary of the passing of my beloved friend Jessica Fetui Corotan. She succumbed to breast cancer after a long, arduous battle with the disease. Jess was love and light embodied. My grief over her death has often taken the form of blurriness: whenever I contemplate her absence, tears of sorrow cloud my vision, and an emotional fog descends over me. Her loss will forever frame the way I see the world.

Sara Phenix. Happier times: Caroline, Jessica & Sara (L-R). 2022.

Sara Phenix. Happier times: Caroline, Jessica & Sara (L-R). 2022.

Consolation came in the same form as grief, though this time outside the confines of the Orangerie. Shortly after Jess’s passing, I walked past the painting Sunset that hangs in the Harold B. Lee Library. Like with so many of the works at the Orangerie, its inviting diffusiveness drew me in. What makes this painting especially meaningful to me is that it was done by Amy Gueck Webb, another dear friend of mine (and a mutual friend of Jess’s), as a way to commemorate the year she spent in O’ahu. She painted this landscape in 2001—a joyful time when we, as a group of friends, formed deep, abiding friendships that have since been the emotional bedrock of our adult lives.

Amy’s seascape depicts the very place where Jess sought wholeness and healing during her cancer battle. It reminds me of how at home Jess was on the beaches of Hawaii and how fitting it was that her ashes were scattered in Kawela Bay during the memorial Paddle Out. Jess’s circle of friends and loved ones was so large that I imagine their collective tears made the ocean swell with sorrow that day.

In the wake of this wounding loss, Sunset signifies for me both the beauty of my friend’s life and the devastation I still feel after her death. Its diffuse forms, amplified by the gauzy haze that now clouds my right eye, are nonetheless layered over a few discernable solid lines. These linear structures are stabilizing forms in the abstracted seascape. They remind me that, though now I see through a glass (or an optical lens) darkly, this much is clear: even among the foggy incertitude of so many unknowns, there are the anchoring assurances that, because of the divine sacrifice, love survives beyond this life and will reunite us in the next.

Amy Gueck Webb. Sunset. 2001.

Amy Gueck Webb. Sunset. 2001.