This post was written by Sawyer Wood, BYU Humanities Center intern and student fellow.

For most of my life, I thought I wasn’t a museum person.

I’d been to plenty of galleries, but I didn’t see what I was supposed to do there. I would stumble through room after room, trying to match pace with whatever school group I was with, often stopping just long enough at each art piece that someone watching might think I was interested. I wanted to be interested, or at least appear so, but I thought I just wasn’t a museum person. Then, about two years ago, I went on a date that changed the way I saw museums forever.

The date happened to be with someone who worked at the BYU Museum of Art. I’d been meaning to ask her out, and I’d heard about a date night happening at the MOA; I decided that was as good an in as I was going to get. We set a day and time to meet, and arrived at the museum’s front desk. I don’t know what I’d expected, but it wasn’t the clipboard that the receptionist handed me. At the top of the page, in red curly letters, it read Date Night Scavenger Hunt. I looked at my date quizzically and she nodded, so I took the clipboard, wondering why we’d need it. I realized the paper had a list of questions, which only further baffled me. Who brought questions to a museum?

The questions weren’t the surface-level stuff you’d expect on a first date, and they weren’t random either. They asked things like “which piece in this room reminds you most of your childhood?” and “tell your date which of the paintings you’d hang in your apartment.” I’d never seen a scavenger hunt like that before, but, to my surprise, I enjoyed it. We didn’t get through more than ten rooms, meaning most of the museum was left unexplored, but the questions were great springboards for conversation, and I connected with the art on a new personal level. I confess I don’t remember much about the girl I was with, and we didn’t go out again. But I’d never enjoyed a museum more. I wasn’t just exploring it, I was exploring me.

About a month later, a professor gave our class an assignment to find a painting at the same museum and stare at it for twenty minutes. I was a little confused by the idea, and, for some reason, the previous MOA date didn’t cross my mind at all. Still, I went, and I picked the painting Fallen Monarchs by William Bliss Baker. I set my timer, looked at the painting, and waited. I waited as my eyes traced the shapes, as the colors blended together. I stepped closer to the painting, then farther away. Then, I looked harder, though that wasn’t a word I would have paired with looking before that day. And, slowly, second by second, the painting changed. I don’t know how else to describe it. Details began to emerge that I hadn’t seen before. There was a sunrise in the background, or maybe a sunset, and I started to wonder why the artist had chosen that. My mind wandered into the symbolism of the name, and I spun webs of possible interpretations. When my twenty minutes was up, I was tired, but I’d also appreciated the painting more than any I’d seen before. I was back on that date again, and this time I hadn’t needed a conversation partner. The art was the conversation.

I tried to keep that date and that painting in mind when I traveled to Portugal this summer on a study abroad. I knew we’d see a lot of museums, and I didn’t want to walk through them the way I once had, anxious to feel cultured. But I fell into old habits, overwhelmed by how much there was to see, and ended up rushing through room after room. I also took pictures of everything, telling myself that I was living a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. After a few museums this way, I knew I needed to change something. I was spreading myself too thin.

I decided to set a limit for myself, and my camera seemed as good a metric as any. I told myself that I could only take two photos for each room we visited, and that they’d have to be the two things I genuinely liked the most. Though it would mean I didn’t capture everything, I hoped it would give me more depth over breadth, and turn the museums from photo opportunities into lived experiences.

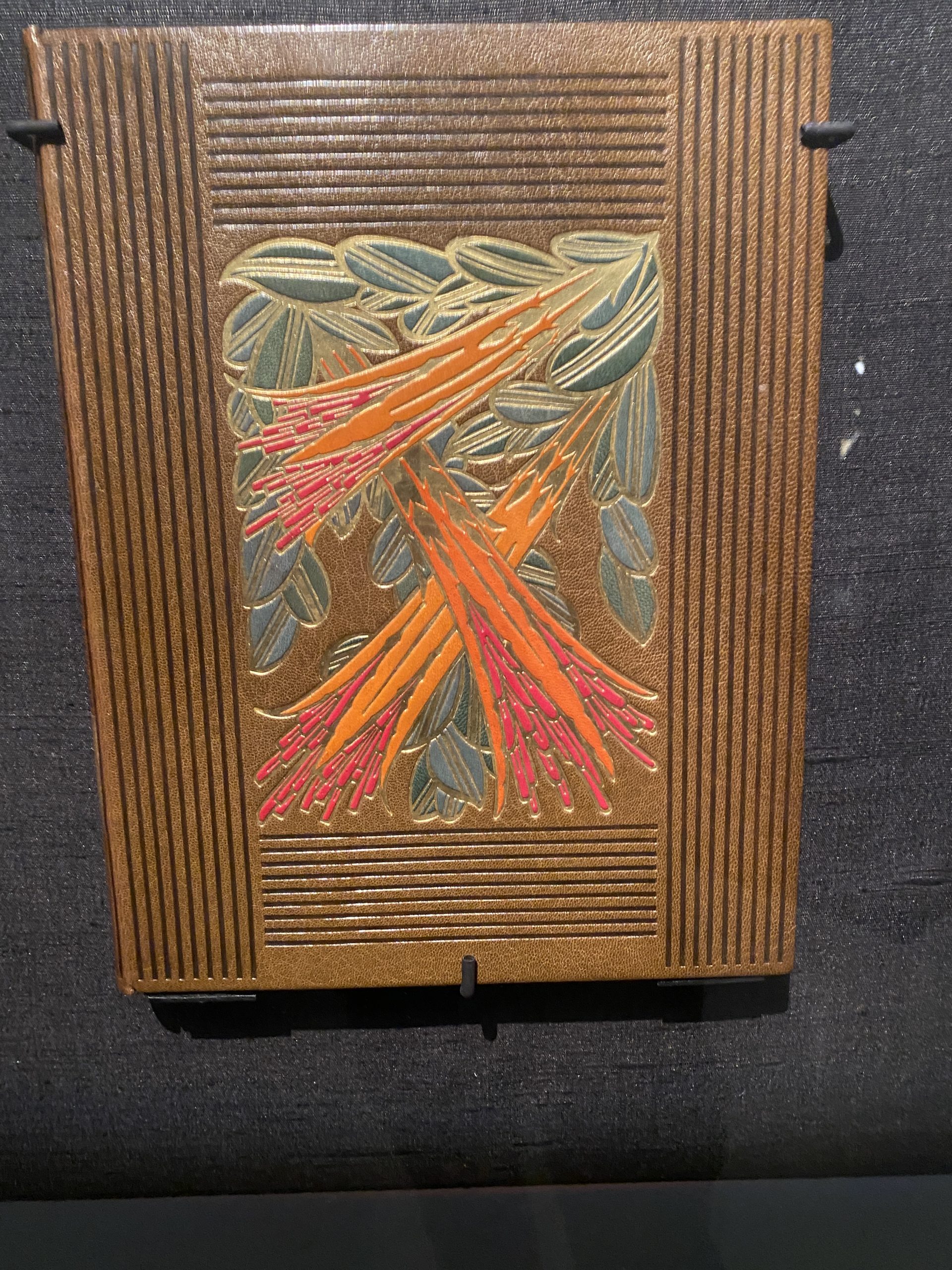

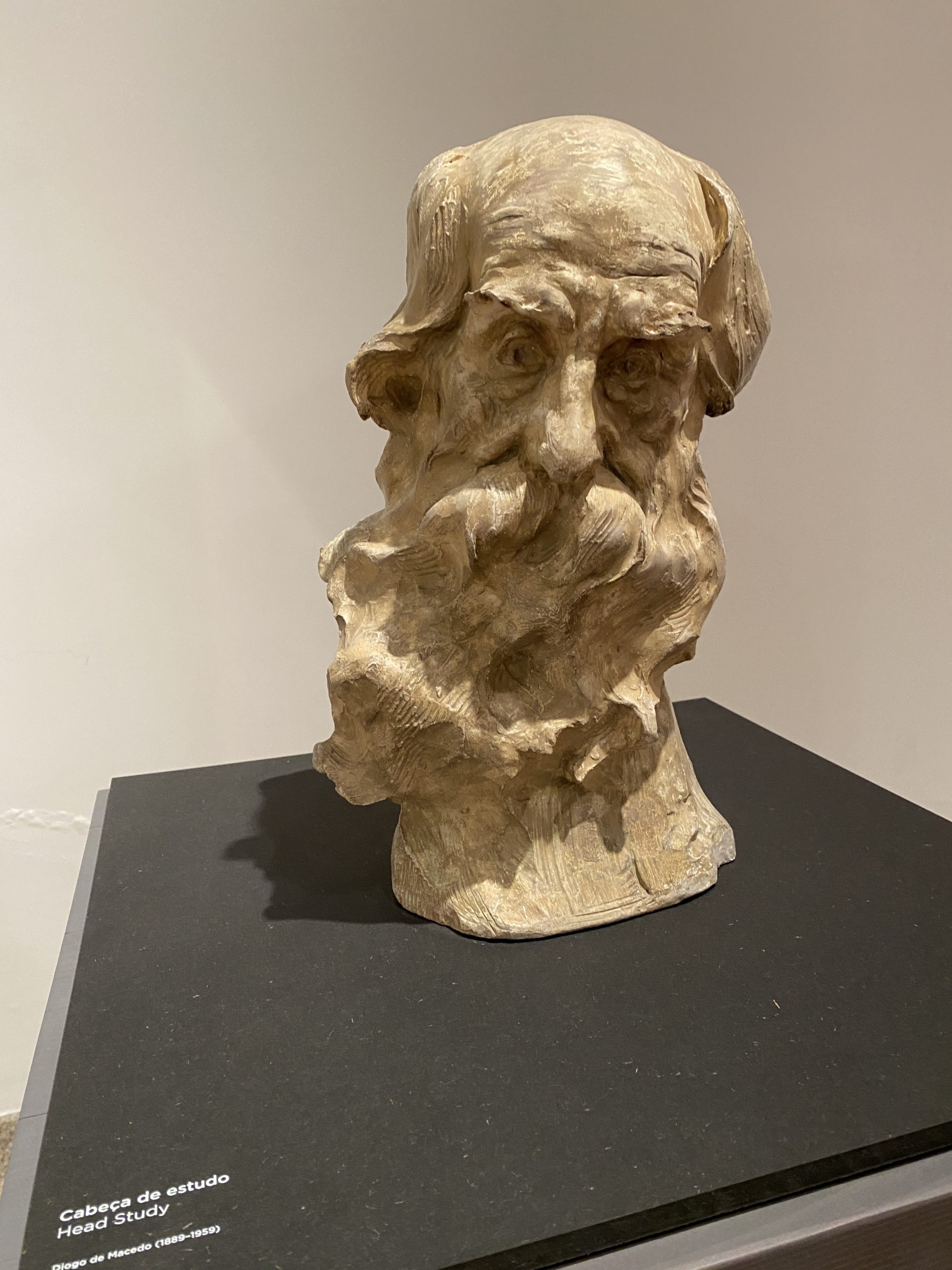

Here are some of the results:

There were many others; I didn’t stop for those.

And despite the pieces I didn’t end up seeing, I enjoyed the museums so much more. This helped me understand something my study abroad director had told us at the beginning of the trip: “Ver menos; Aprender mais.” See less; Learn more.

Too often, I fool myself into thinking that seeing more art means I appreciated a museum more. I’ve realized that this stems from insecurity, from the feeling that I don’t actually belong in a museum. I’m afraid a well-dressed security guard is going to arrive at any moment, say, “you’re not cultured enough to be in here,” throwing me over his shoulder and hauling me out. My skimming of hundreds of art pieces isn’t really engaging with any of them, it’s just me trying to keep ahead of that guard. I’m pretending that I understand and appreciate all the depth of a piece or an exhibit in one glance, and need nothing more than that, in hopes that that guard will buy my act and let me stay.

But stopping in front of an art piece, or circling back to one of a few that stood out, is an admission that I don’t know everything about them yet, that there’s something more to learn. The humility is what makes it work. It’s like saying to the art, “I don’t understand you, and I want to.” And like the scavenger hunt date, like the twenty-minute staring session, I’d say that’s something worth doing.

References

Baker, William Bliss. Fallen Monarchs. 1886, Brigham Young University Museum of Art.