This post was written by Charlotte Stanford, HC Fellow, Department of Comparative Arts & Letters

When I say I am a medievalist and that I am interested in the study of medicine, I often encounter skepticism—if not a frisson of actual horror. Wasn’t that an age that practiced bloodletting? That didn’t believe in bathing? That lived in squalor worthy of a Monty Python skit, complete with dead cats?

Well, yes, their paradigms of health were different from ours, and some of their practices were crude and unregulated compared with the precision of modern methods, but there is a kind of arrogance in assuming that people of the past were unsophisticated and ignorant because they followed different paradigms than we do now. In a recent read inspired from one of our Humanities Colloquium series speakers (Norman Wirzba) who recommended The Hidden Half of Nature: The Microbial Roots of Life and Health, by David R. Montgomery and Anne Bikle, I was fascinated to learn how much microbes impact our health, and how contemporary science is just beginning to dip below the surface of a rich and complex world that we as yet only fractionally understand. It behooves us, I think, to keep an attitude of humility towards ourselves, and remember we might view our own age very differently from the vantage point of future knowledge—what assumptions do we make that people of the future will find as shocking (or risible) as bloodletting?

With that in mind, there are aspects of medieval healing from which I draw inspiration, and which I find of value in my own life. One of these is the holistic approach of treating body and soul, and the other is the incorporation of powerful works of art, especially religious art.

The medieval era was, famously, an age of faith, when Christian beliefs mingled with and shaped all aspects of society. Seeking healing in such an era meant seeking the solace of religion as well as of medicine—the two were inseparable. Medieval charity hospitals, accepting poor patients, required as a first step towards cure that the sufferer make confession to a priest. Sin could not only impede recovery, it was, in a sense, the root cause of all illness in this mortal world.

The mortal world was, moreover, very delicately balanced, and the human body no less so. The famous paradigm of the four humors comes to play in understanding this balance. These four concepts, developed by Galen (a Greco-Roman physician of the second century), consist of blood, yellow bile, black bile and phlegm. They correspond to elements (respectively air, fire, earth and water), degrees of heat, cold, wetness or dryness, and, of course, emotions. The cheerful sanguine temperament was associated with a propensity toward blood, furious choler with yellow bile, sad melancholy with black bile, and sluggish chill with phlegm. This model remained influential from the classical era down through the Victorian, and was so commonly understood that it needed little if any explanation in common speech. Any reader of Shakespeare comes quickly to understand the importance of the concept, as when Petruchio comments ironically on his own outburst over an ill-cooked dinner: “I tell thee, Kate, ’twas burnt and dried away/ And I expressly am forbid to touch it/For it engenders choler, planteth anger” (Taming of the Shrew IV, i).

Adjusting diet, was, of course, a key treatment in balancing the humors. It was part of the whole environment considered by physicians when assisting the ill to recover. These factors were embodied in the principles of the six “non-naturals” (so-called because they are not essentially inherent to the body and its nature): air, food and drink, sleep and watch, motion and rest, evacuation and repletion, and passions of the soul. Striking the proper balance between all of these—and taking into account the patient’s own natural complexion, or propensity toward one or more of the humors—was a careful task that required thought, patience and no small amount of individual calibration.

The best physicians’ careful crafting of the ideal balanced regimen was normally available—as is the case with modern medicine—only to the wealthy. However, medieval people also had charity hospitals, and some of them boasted every amenity the donors’ money could buy. The founder of the early sixteenth-century London hospital of the Savoy, Henry VII, provided furnishings that reflected his own magnificence. I have studied the building accounts of the Savoy, and details of the structure’s beauty gleam out of the long lists of purchases and costs: “paid unto John Elmer for makyng off 2 howses for 2 ymagez to Stonde in the North ende off the Cross Ile in the hospital… paid to Rawffe Bowman for makyng off 10 angels off stone for the corbells for the grete howse for pooer menys bedds, le pece 3s 4d” (Westminster Archives and Muniments MS 63509, fols. 140; 20). I imagine looking up at these soaring angels hovering over the beds, the elaborate tabernacle niches housing figures of saints flanking the altar, the skilled labor of these craftsmen making the place one of rest and beauty.

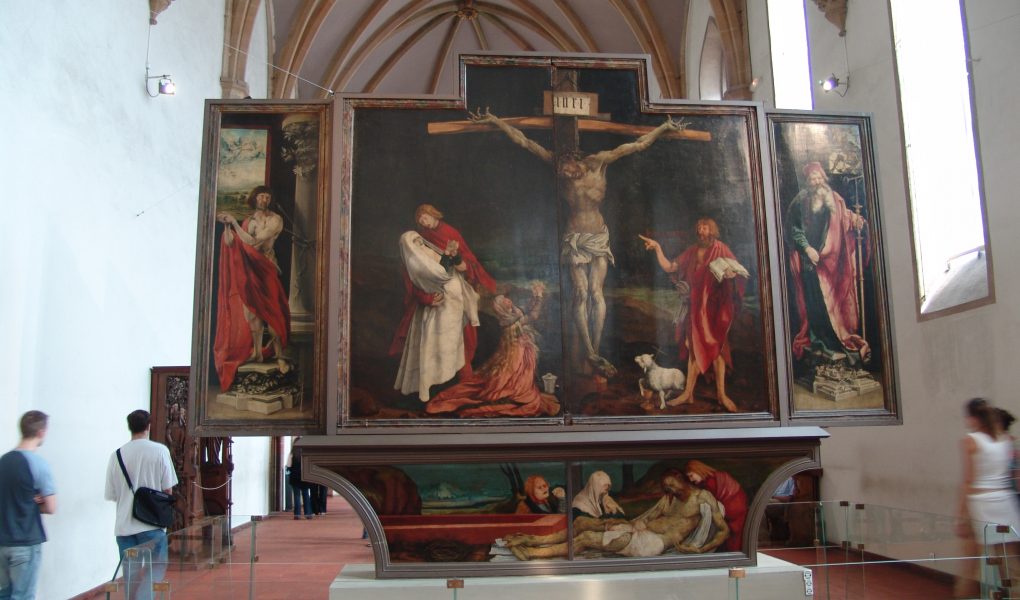

Sadly, most of the beauty of the Savoy hospital has vanished, but other examples still retain traces of impressive art and architecture, like the rich frescoes of the hospital of Santa Maria della Scala, Siena, or the exquisite tile roofs and panel paintings of the hospices de Beaune. For me, though, the most dazzling instance is Matthias Grünewald’s Isenheim altarpiece. It is roughly contemporary with the Savoy (ca. 1512-1516) and was created for the hospital of St. Anthony in Isenheim, near Colmar in the region of Alsace, France. I have been fascinated with this work ever since I was first introduced to it in a BYU Humanities class. I recall how professor John Green explained that the sufferers of “St. Anthony’s fire” (caused by eating grain contaminated with ergot) developed hideous skin sores akin to the gruesome wounds displayed on the crucified Christ. While most of my classmates recoiled from the grim distortions embraced in this image, the most heart wrenching crucifixion I have ever seen, I was fascinated by the bonds of empathy Grünewald forged between his art and these sufferers.

Years later I am privileged to visit Colmar. Finally I see the Isenheim altarpiece in person. It is astonishingly compelling. The figures are life size and Jesus’ twisted feet are poised near eye level, the first thing I see. Only later does my eye move up to his livid face, bruised and discolored, and then out to his hands. The break in the double panel, just at the right arm, recalls the amputations practiced on severe cases of St. Anthony’s fire, as does the disjointed break in the predella below, dividing Christ’s lower legs beneath the knees. I look upward and outward at his hands, spasming open in an agony that is echoed by the anguish of Mary Magdalene’s sorrow, wringing her own hands expressively at the foot of the cross. Surely Matthias Grünewald could visualize suffering; this painting, above all others, brings home to me the connection between viewer and artwork, between the limits of mortal endurance and God’s limitless love. To me, this is beautiful.

But the artwork also offers other visions of beauty and healing, in particular one that radiates peace instead of pain. The altarpiece, like most of its kind, would have remained closed, with the outer scene displayed on ordinary days. On feast days, however, the inner wings would have been opened to display a different story, with a different message. The Isenheim altarpiece has, in fact, two sets of wings, but the response to the sorrow and pain of the crucifixion is found on the central set. The spread scenes originally showed a sequence of Annunciation, angel musicians, Nativity and Resurrection, but in the museum they have been disassembled to allow viewing of all panels in turn. I turn instinctively to the Resurrection, where the darkness explodes into light. Christ floats above a burst stone sarcophagus, an orb of glory like the sun radiating behind him so brightly the paint seems luminous. I have to squint, and I wonder, how does the painter manage such an effect? Christ’s face shines serenely and the wounds in his upraised hands glow like rubies. His face is the same face as Mary’s, and I wonder why I have never noticed an artist show this so clearly before. His skin is like alabaster, all traces of pain gone.

To say that the open altar helped the sixteenth-century hospital patients feel hope rather than despair is true. Words feel flat, however, compared to the images presented before my vision. I do not suffer from St. Anthony’s fire. I live in an era that frames disease in a very different way, one that considers the cleanliness of the body far more significant than cleanliness of the spirit. But when I look at the Isenheim altarpiece I get a glimpse of what it might feel like to see the world a little differently, and I exit the museum, feeling humbled and healed.