This post was written by Jamie Horrocks, a Humanities Center faculty fellow.

I am scheduled to teach a class on the Victorian novel next semester. Because of this, I have spent the past few weeks stewing over the question that surely all English professors in my position stew over: what is the maximum number of words that I can ask—in good faith, and without fear of recrimination, refusal, or recourse to audiobook at 2.5x speed—a busy but generally well-intentioned undergraduate to read in a fifteen-week semester?

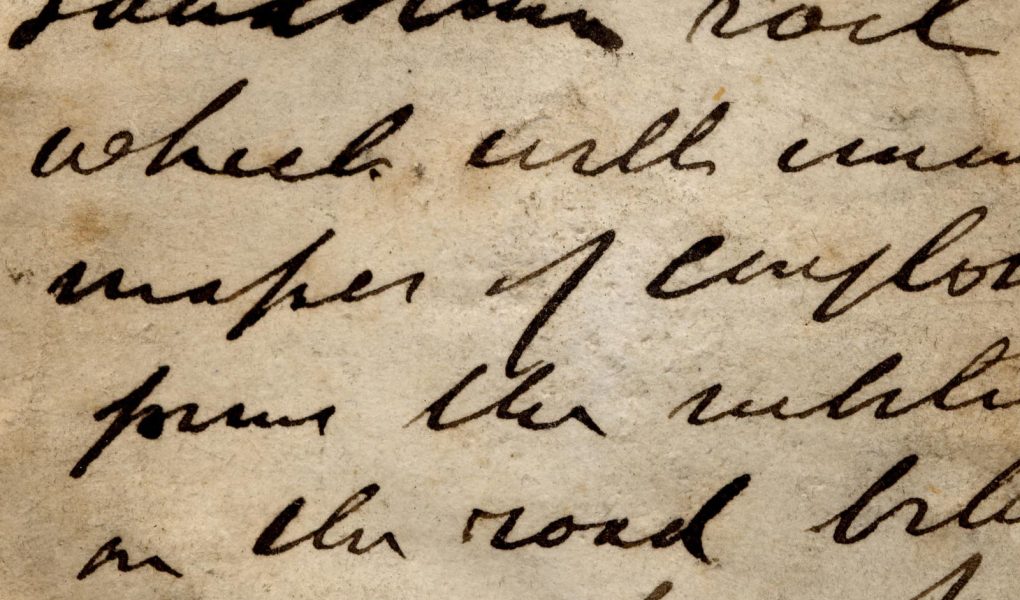

Victorian literature is not for the faint of heart or the scant of time. The Victorian novel revels in words. It glories in the turn of phrase that can sustain itself without a period for three-quarters of a page. It says, “Why one volume when there could be three?” My copy of Brontë’s Villette clocks in at a respectable 672 pages, or some 171,000 words (English glossary of French words not included). My Penguin edition of Middlemarch sprawls across 912 pages, or about 228,000 words. My Bleak House tops this with 1,036 pages, which amounts to something like 356,000 beautifully Dickensian bits of phonotactics. Five The Sun Also Rises-es could fit into Bleak House, with room to spare for an extra round of drinks. Six slender To the Lighthouse-es could be tucked inside its capacious covers.

This is not because Charles Dickens was paid per word (he wasn’t), or because nineteenth-century middle-class readers had nothing better to do (they did). Rather, it was because for a while, many writers believed—and readers agreed—that capturing the “real world” was the essential task of the novelist. And the world, in all of its complex reality, is a mighty big place. In addition, some came to suspect that the words that formed the realist novel were, in fact, the constructive material of reality itself. Consider what George Eliot says of Hetty Sorrel, from the novel Adam Bede: “Hetty had never read a novel; if she had even seen one, I think the words would have been too hard for her; how then could she find a shape for her expectations?” No fictions, no forms for one’s thoughts, hopes, or dreams. The equally tenuous expectations of Dickens’s Pip likewise rely on Pip’s ability to narrate, to fill up pages with words that stand in for the otherwise misty, marshy “broad impression of the identity of things.”

I was reminded of Pip’s difficulty in putting reality into words that his “infant tongue” could manage a few weeks ago when the children in my Primary performed their annual program in Sacrament Meeting. As Primary President, I was responsible for writing the script, but I was uncomfortable making up words to put into the mouths of the children. So my counselors and I interviewed each child, recorded their answers to different age-appropriate questions, and sent these replies home to parents for practice.

The phone calls and texts began almost immediately. They were polite but pointed. All came from the parents of senior Primary children, and all shared the same refrain: “My child cannot say these words.”

The problematic words, I discovered, were the replies several 9, 10, and 11-year-olds had given when we asked them to share an experience they had had this year that prompted them to turn to Christ for help, solace, or understanding. The children had responded idiosyncratically but honestly, telling us of the triumphs and defeats, fears and frustrations, that color the contours of childhood. They reported sharing their worries with parents and other trusted adults, who guided them through the processes of prayer and reflection that move beyond the “lost toy” or “scary sound in the night” episodes that structure the faith experiences of younger children—the appeals we make to God when we know the toy won’t or can’t be found. Their stories mostly ended with recognitions of the superlative indifference of ordinary life: the spelling tests were still a struggle that required daily, dogged effort; the loneliness of losing friends to a long-distance move still pricked; the unkind peer was still unkind; the beloved pet shuffled off its mortal coil.

These are, of course, the narratives that comprise the realist novel, that supremely mundane genre that threw off epic conceits, historical actions, supernatural interventions, and romantic idylls. They are the “drudging, daily, common things,” as Christina Rossetti put it, that the realist literary mode extols. They attempt to find in the real something true, in the individual something representative . . . and therein lay the problem. By putting their experiences into words, the children exposed something shell-less and half-formed, something vulnerable to judgment and, perhaps, disparagement. Parents wanted, needed, to protect. They did not want their child to be known to the ward as the one who struggled in school, the one who was bullied, the one who felt alone or afraid or lost. So independently of each other, all asked, “Can I change the words that my child will say?”

When I readily consented, I found myself witness to an unexpected revision. I watched as parents exchanged one kind of story, one kind of realism, for another. Personal narratives were supplanted with more amenable statements that posed no risk to the innocent: “I know Jesus loves me”; “The Holy Ghost helps us”; “God listens when we pray.” These phrases are unimpeachable; no believer could object to the goodness, the rightness, of these words. And yet I was saddened, not by the loss of truth—for truth there still is here—but by what struck me as the benevolent replacement of words true with what the poet Philip Larkin described as words “not untrue.”

In an era of deep fakes and crisis actor claims that challenge the veridical status of all representations of reality, the difference between words true and words not untrue may be so slight as to be meaningless. After all, there was no real loss in our Primary program. Possibly there was positive gain in terms of the mental wellbeing of children. If I’m honest, I’ll have to admit that I, too, occasionally slide from truth to not untruth, and not always with the most benevolent of intentions. Such evasions feel, inevitably, evasive.

But they might, Victorian novelists suggest, enable us to manage the sometimes-overwhelming realism of the real. In Middlemarch, George Eliot famously expostulates that “If we had a keen vision and feeling of all ordinary human life, it would be like hearing the grass grow and the squirrel’s heart beat, and we should die of that roar which lies on the other side of silence.” You and I cannot register everything. This is the paradox of the realist novel: no number of words can capture the fullness of even the most ordinary life. Knowing this, perhaps the replacement of words true with words not untrue is inevitable. Perhaps it is even necessary for preserving our own mental wellbeing, shell-less creatures that we all are.