In spring 2021, a Saudi man named Sultan Aldeet netted himself one million Emirati dirhams (roughly $273,000 USD) plus a symbolic cloak and ring. His achievement? Winning first place on Prince of Poets, an American Idol-inspired TV contest in the United Arab Emirates between classical Arabic poets.[1] It airs every other year from Abu Dhabi and gets millions of viewers. A similar competition is Million’s Poet, also in the UAE and featuring Emirati dialect poetry called “Nabati,” which differs in word choice and accent from classical Arabic and other Arabic dialects.[2]

Both shows are political lightning rods, with poets drawing fire for their criticism of Arab leaders. In 2010, a Saudi woman named Hissa Hilal faced death threats after reciting her poem “The Chaos of Fatwas,” in which she blasted arbitrary rulings by Muslim clerics. She took third place, including a prize of three million dirhams (about $817,000 USD), and inspired people everywhere, especially women, to speak out against bigotry and censorship.[3]

in the Arab world, poetry is big business.

To the English-speaking West, the word “poetry” evokes Hallmark greeting cards, or at worst, fearful high schoolers cramming for tests about old books with no link to reality. But in the Arab world, poetry is big business. Sometimes it’s even a matter of life and death. “The authority of verse has no rival in Arabic culture,” write Robyn Creswell and Bernard Haykel.[4] This fact alone makes Arabic poetry, and classical Arabic literature generally, worthy of note.

Yet Arabic readers would have small potatoes if all they did was use literature to fathom current events. The fact is, classical Arabic represents a cultural heritage all on its own. For some 1,500 years it has been the language of religion and learning and empire. It’s the earliest poetry tradition to have rhyme other than Chinese. It’s one of the wonders of the world, to rival the Colosseum or the Taj Mahal. And like other monuments, classical Arabic literature can—and should—be visited over and over, out of reverence for its fullness of action, thought, and feeling.

In the 6th century, before the coming of Islam, Arabic poetry sprang Athena-like out of nowhere from Arabia’s desert sands. It conjures images of mounted Arab warriors who prized manly virtue, muruwwa, and who obsessed over revenge, honor, and loyalty. “War was effectively a religion,” writes Cambridge University Professor James Montgomery.[5] But love and fate also preoccupied the poets. Generosity was their crown jewel. They trained their focus on the natural world; just listen to the poet-king Imru’ al-Qays describe a terrible downpour:

It battered the tallest trees to the ground

Like old men knocked on their beards…

The folds of rain looked like tribal leaders

In the long striped flow of their jubbah robes.[6]

Supposedly each year, poets vied for glory in an annual contest—not unlike today’s Emirati TV shows—and for the right to have their poems stitched in gold and suspended in the Kaaba shrine at Mecca. These are the hanging odes, mu`allaqat, and they still have bedrock status like Beowulf does in English.

Poets vied for glory… and for the right to have their poems stitched in gold…

With the arrival of Islam, Arabs gathered themselves into cities and courts. Arabic literature followed suit, taking up urban themes like drinking parties and praise for rulers. Poetry reigned supreme, but essays and letters came into their own. The great 9th century prose stylist Jahiz wrote about language, philosophy, and theology, but also dogs, fish, mice, backs and bellies, round versus square, the boasts of Blacks against whites, the blind and the squint-eyed, hatred and jealousy, and more. Hence, he’s sometimes compared to Montaigne, the father of the essay and who described himself as having “a mind like a runaway horse.” Here is Jahiz praising books:

A book is a companion that does not flatter you, a friend that does not irritate you, a crony that does not weary you, a petitioner that does not wax importunate, a protégé that does not find you slow, and a friend that does not seek to exploit you by flattery, artfully wheedle you, cheat you with hypocrisy or deceive you with lies.[7]

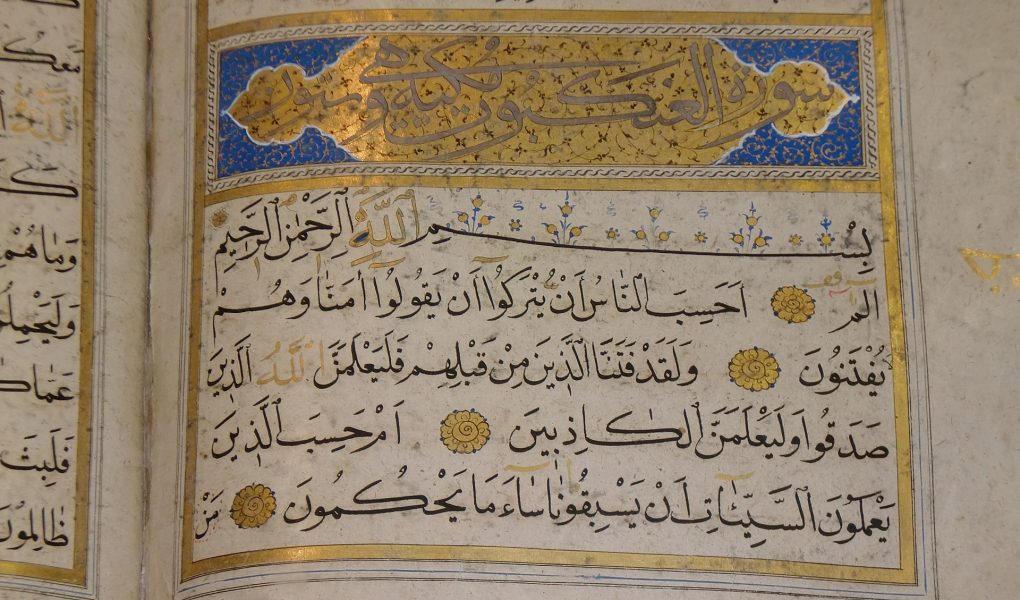

In later centuries, Arabic prose was perfected by chancery scribes, that is, state officials who crafted formal correspondence. Writers like al-Qadi al-Fadil (12th century) and Ibn Hijja al-Hamawi (15th century) dressed up their letters to fit a given theme. For example, Ibn Hijja’s ornate letter Yaqut al-kalam, “The Ruby-Red Report,” bears witness to the burning of Damascus during the 1390 siege of Sultan Al-Zahir Barquq and is appropriately stocked with puns about fire, including quotes from the Qur’an Chapter 44, entitled, “The Smoke.”[8]

These are just a few of classical Arabic literature’s endless riches. It is hard not to be charmed by them. In fact, the best reason to discover classical Arabic literature may be that it’s fun to read. Curious explorers will enjoy the morsels gathered in Night & Horses & the Desert edited by Robert Irwin, and Classical Arabic Literature: A Library of Arabic Literature Anthology, selected and translated by Geert Jan van Gelder. But beyond that, perusing anything written long ago lets us commune with the dead, both for our sakes and theirs. The greatest act of respect is to not forget them and to keep speaking with them. In the pleading words of 19th century poet Hasan Quwaydir al-Khalili:

These are our works, these works our souls display;

Behold our works when we have passed away.[9]

This post was written by Kevin Blankinship, Assistant Professor of Asian and Near Eastern Languages, Brigham Young University.

Works Cited

Abdel-Kader, Ali Hassan, ed. and trans. The Life, Personality, and Writings of Al-Junayd. London: E.J.W. Memorial Trust, 1962.

`Antarah ibn Shaddad. War Songs. Trans. James E. Montgomery. New York: New York University Press, 2018.

Creswell, Robyn and Bernard Haykel. “Battle Lines.” The New Yorker, 1 June 2015. Accessed online 26 October 2022: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/06/08/battle-lines-jihad-creswell-and-haykel.

Irwin, Robert, ed. Night & Horses & the Desert: An Anthology of Classical Arabic Literature. New York: Anchor Books, 1999.

Jamil, Basant. “Al-Sa`udi Sultan Aldeet yahsid laqab ‘Ameer al-shu`ara’’ fi al-mawsim al-taasi`” (Saudi man Sultan al-Deet reaps the title of ‘Prince of Poets’ in season 9),” Al-Youm al-saabi`, 7 April 2021. Accessed online 26 October 2022: https://bit.ly/3E6SY6Y.

Moezzi, Melody. “Hissa Hilal Fights Fatwas With Poetry.” Ms. Magazine, 24 March 2010. Accessed online 26 October 2022: https://msmagazine.com/2010/03/24/hissa-hilal-fights-fatwas-with-poetry/.

O’Grady, Desmond. The Golden Odes of Love: Al-Mu`allaqat. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, 1997.

Pomerantz, Maurice A. “The Rivalrous Imitator: The Ruby-Red Account of the Fire of Damascus by Ibn Ḥiǧǧah al-Ḥamawī (d. 838/1434).” In The Racecourse of Literature: An-Nawāǧī and His Contemporaries. Ed. Alev Masarwa and Hakan Özkan, Baden Baden: Ergon Verlag, 2020. 129-146.

Footnotes

[1] Jamil. “Al-Sa`udi.”

[2] Twenty-two countries have Arabic as their main language, and each has a distinct dialect.

[3] Moezzi, “Hissa Hilal.”

[4] Creswell and Haykel, “Battle Lines.”

[5] `Antarah, War Songs, xxx.

[6] O’Grady, Golden, 11.

[7] Irwin, Night, 88.

[8] Pomerantz, “Rivalrous.”

[9] Abdel-Kader, Life, v.