This article is written by Matthew Ancell, a Humanities Center faculty fellow.

Amidst the wars of religion instigated by the Protestant Reformation, two emissaries, Jean de Dinteville, Francis I’s ambassador to England, and his friend Georges de Selve, the future Bishop of Lavaur, were sent to the court of Henry VIII in 1533 to dissuade the English monarch from severing ties with the Roman Catholic Church. The German artist Hans Holbein the Younger (c. 1497–1543), the king’s court painter, commemorated the occasion with a portrait commonly called The Ambassadors (see Figure 1). The painting is the most famous case of the artistic technique of anamorphosis, and I believe, the best visual emblem of this liminal status between two religious and political systems, marking a crucial moment in the events leading to the English Supremacy, establishing Henry as the head of the Church of England and completing the break from Rome.

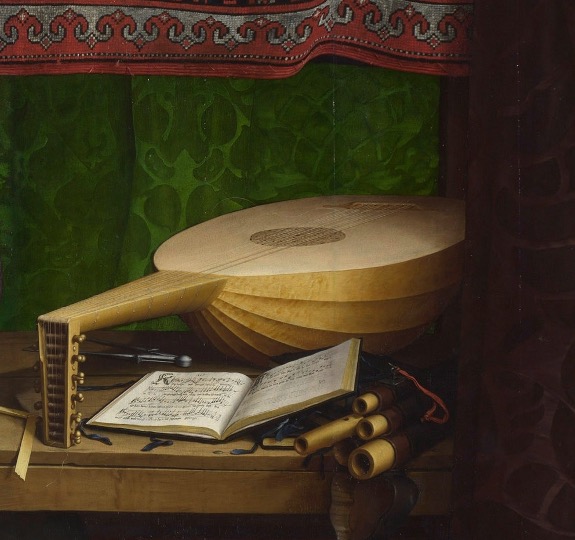

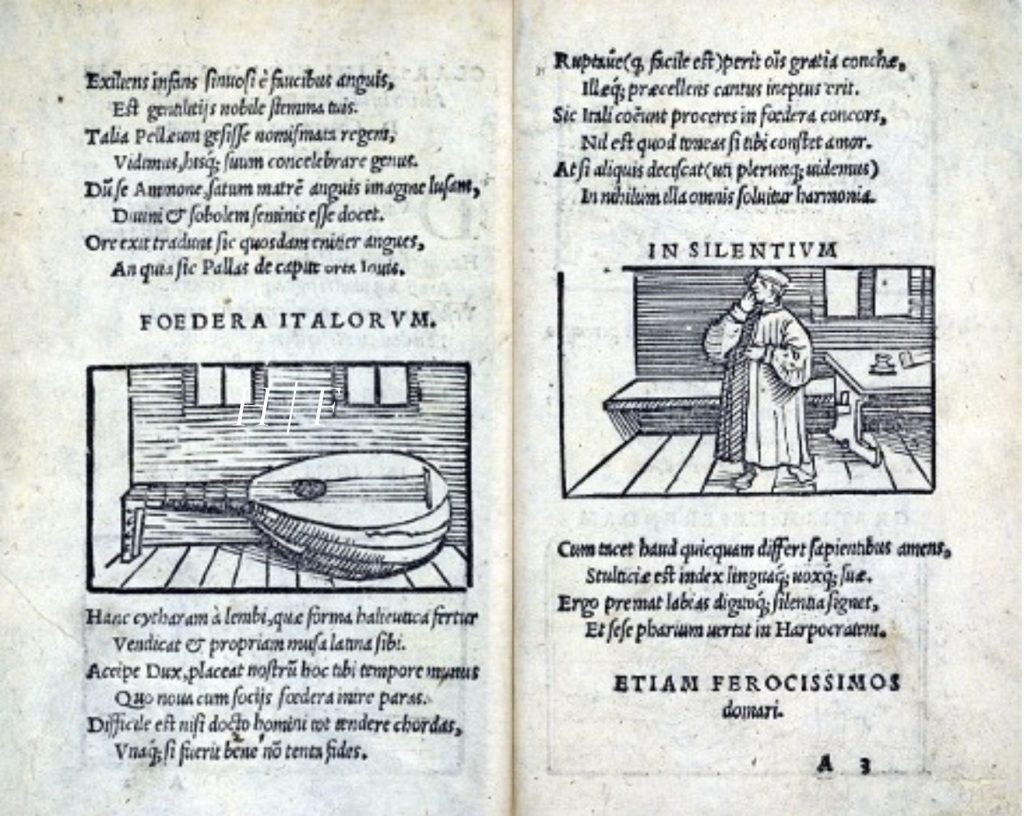

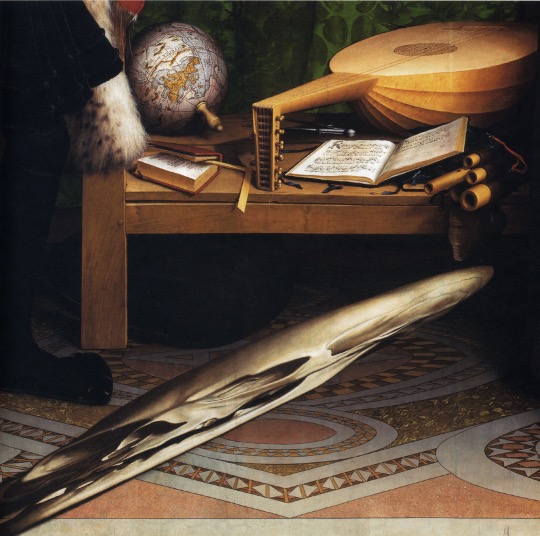

The two ambassadors bookend a pair of shelves supporting objects that represent astronomy and mathematics above, and geometry and music (the last four of the seven liberal arts, or quadrivium) below. This division of the quadrivium into celestial and terrestrial planes reinforces the sympathy between the subjects, and presents an orderly cosmos, governed by mathematics, which informs the other three disciplines, geometry, music, and astronomy. Overall, the richly detailed oil painting, rendered in satisfying perspective, presents an ostensibly balanced image of human worldly accomplishment, ignoring, of course, the distorted (anamorphic) skull floating in front of the young men. The skull aside, however, upon closer inspection, other details trouble the harmony. First, the lute not only functions to demonstrate Holbein’s mastery of linear perspective—since the lute’s irregular shape is difficult to foreshorten—but also notoriously sounds a discordant note with its single broken string (see Figure 2). Andreas Alciatus’s emblem of 1531 (see Figure 3) reinforces the point about lack of harmony, as the text explains, a lute with an out of tune or broken string can only produce discord and compares the effect to the harmony of political alliances “dissolving into nothing [In nihilum illa omnis solvitur harmonia].”

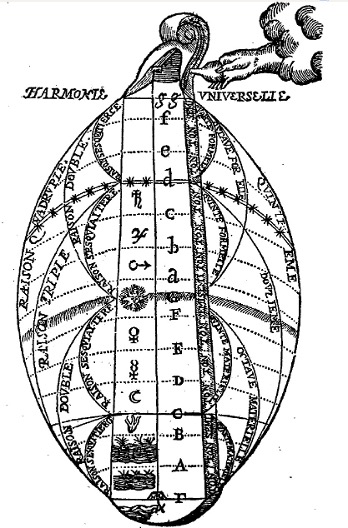

The pervasive Pythagorean and Platonic ideals of the music of the spheres merge with the lute in this illustration of Marin Mersenne’s Universal Harmony of 1636 (see figure 4), wherein we see God’s hand tuning the instrument constituted by phases of the world “arranged with their elements in octaves, chords and scales.”[1] I have always taken the empty lute case under the table to be Holbein’s doubling down on his perspectival mastery, but Jurgis Baltrušaitis sees it as working in conjunction with Mersenne’s Great Lyre to provide a key to understanding the painting, arguing that the “empty lute-case placed flat in the shadow of the lower shelf behind the skull at the feet of Holbein’s Ambassadors, signifies the stilling of all the science and harmony represented by the instrument,” exemplifying the transition from cognizance of human scientific folly to philosophical doubt.[2]

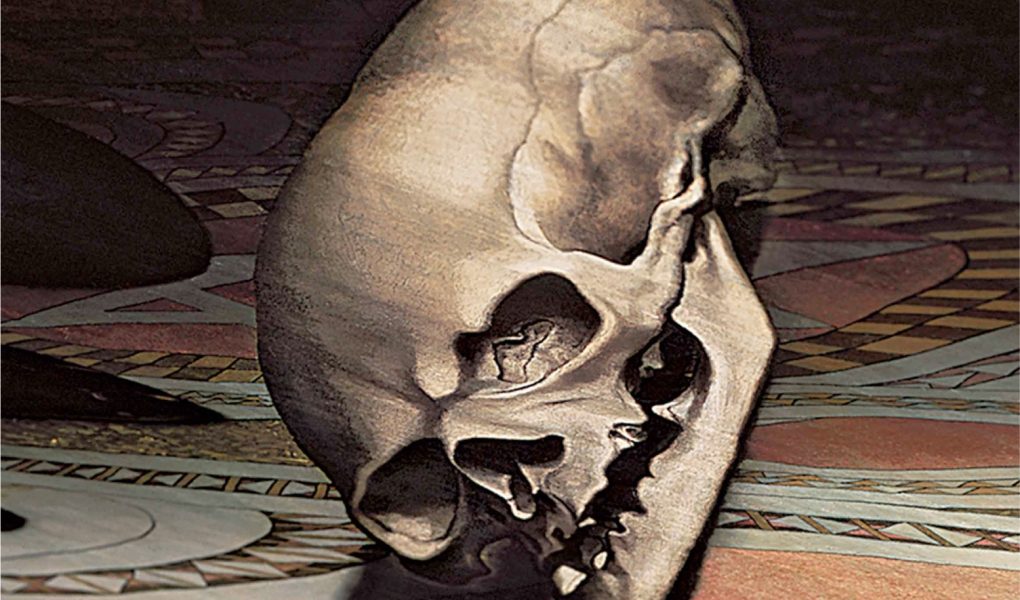

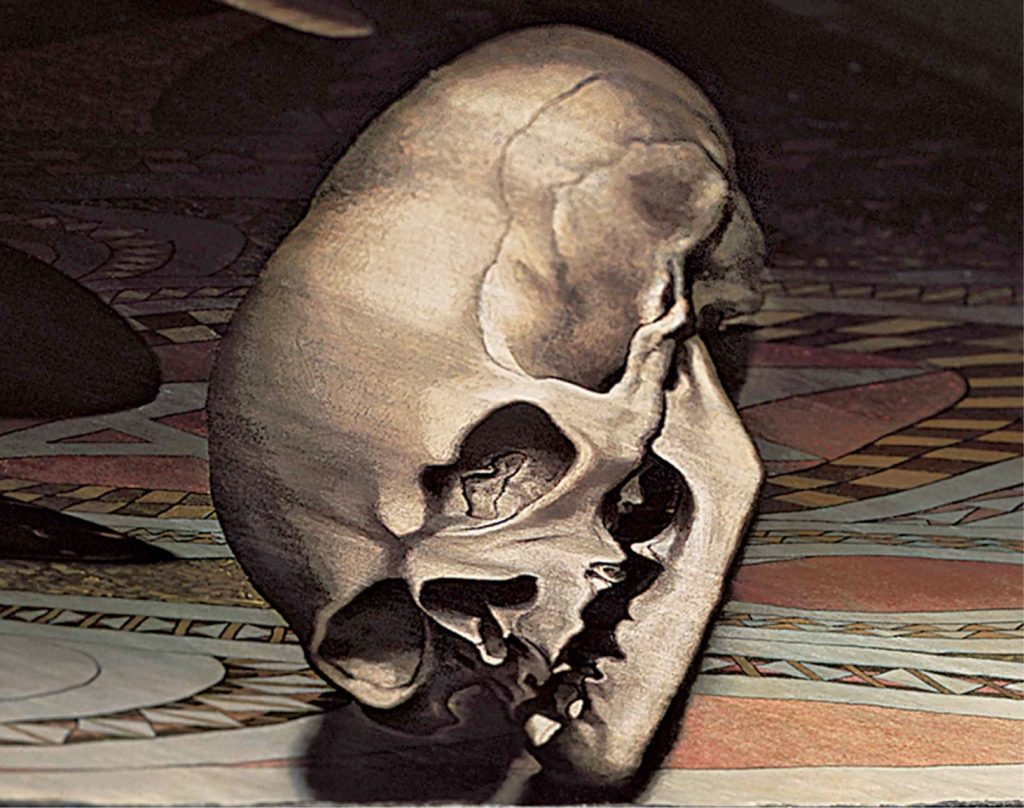

Fundamental to this painting, then, is an understanding of anamorphosis, as both an artistic technique of distortion based on the principles of linear perspective, and as a conceptual model that challenges the assumptions upon which linear perspective, as usually figured by post-Renaissance thinkers, rests. Anamorphosis refers to the way an image, by means of the geometrical principles and methods of linear perspectival representations taken to their logical extremes, is intentionally distorted, but can be reformed by the assumption of an oblique vantage point or through the use of curved mirrors (known as catoptrical anamorphosis). The term literally means “distortion” or “reformation.” Reconstructing the image requires the right point of view. In the early-modern period, anamorphosis interrogated both the ontology and epistemology of representation. Artists employed anamorphic techniques to, among other reasons, conceal messages and present visual arguments in a skeptical mode. In a phenomenological mode, Anamorphosis demonstrates our positional and contingent knowledge, pre-empting Cartesian presumptions of a disembodied subjectivity. That is, our embodied state limits our perception to the phenomena we experience from our mortal and incomplete point of view.

The painting can be considered as a two-act play; a spectator begins the first act by entering through a main door and seeing the two nobles from the painting from a set distance, as if on a stage at the back of the room. While impressed by the display of worldly accomplishment and wealth, as well as the naturalism of the work, the visitor notes the anamorphic figure near the floor (see Figure 5). Advancing, the visitor observes increasing realism in the details, but the object only grows more mysterious. The second act begins with the spectator exiting through the door to the right, troubled by the enigma, and then glancing back at the previous room to discover the human skull in proper proportion, a symbol of the death and the end of the play (see Figure 6). While this “plot” depends partly on an unverifiable in situ analysis, it firmly situates The Ambassadors in the tradition of vanitas, the vanity of earthly power as indicated by the two diplomats themselves, but also the vanity of knowledge as formulated by the Catholic Erasmus (c.1466–1536) in The Praise of Folly (1509).[3] Erasmus and Luther famously debated, with Luther arguing for certainty in scriptural interpretation (namely his own) and Erasmus contending that Holy Writ can be ambiguous and we should suspend judgment and defer to Church authority.

Situated between heaven and earth, the ambassadors and their worldly accomplishments, indeed the whole world, fall into chaos and incoherence, as we contemplate the ephemerality of life and the hope of the hereafter. As such, I read the painting as a skeptical allegory of the epistemological crisis of the Reformation. The memento mori embedded in the work is not just another troubling of the vanity of human accomplishment, wealth, and youth, as presented by the perpendicular view of the work, but also a demonstration of the precariousness of religious affiliation, and—to at least the same degree—faithful conviction in the face of uncertainty. By presenting us with two possible vantage points, one from the perpendicular view, and the other from the oblique, The Ambassadors puts into question the coherence of our perceptions and presents the ambivalence of the skeptical dilemma by asking the viewer to assume an alternate position in order to bring part of the image into focus. Neither position is privileged, and the viewer is forced to confront the dilemma of choosing which position is the correct one. As the vantage points are irreconcilable, whatever position the viewer adopts obviously distorts the view of the other. Anamorphosis, in disrupting the distinction between reality and appearance, displays the essentially positional nature of human understanding. Whether one is Catholic or Protestant was a matter of life and death, depending on the circumstances, but also a matter of salvation or damnation. The problem, of course, is that the truth of the matter is inaccessible from any terrestrial point of view.

John North has established that the elements of the painting signal a horoscope of 4:00 p.m., 11 April, 1533. In other words, Good Friday, just after Christ’s death. He also argues that tracing the line of sight upward from the oblique vantage point to the right of the picture (from which one must view the skull in perspective), it traverses several significant objects in the composition and arrives at the left eye of Dinteville, and the left eye of Christ.[4] Various critics have noted that skull’s shadow falls in the opposite direction compared to others in the painting, which “may serve to indicate the presence of an object from a dimension beyond the temporal.”[5] I would counter that while there is such an object, the crucifix, even Deity is in His most human form, dead on the cross, connecting the schism between heaven and earth, human and divine. The object, or rather the subject, outside the picture plane is the viewer, although the painting forces us to confront our corporality and finitude as we move close to the wall to resolve the image. The oblique vantage point is fixed as the proper position in which to view the anamorphic skull in perspective (see Figure 7). In my view, this structure reinforces the sense of limited mortal understanding, with the only true perspective, that of God, revealed behind the rent veil of the temple at Christ’s death, unavailable to us, embedded as we are, in the phenomenal realm (see Figure 8). Such a realization should humble us, in that just as both the perpendicular and oblique points of view are both correct in a sense, they are also incomplete, lacking the other’s point of view as well as the inaccessible vantage point of the Divine. Understanding the limits of our understanding, no matter how correct, puts us in a position to receive revelation, whereas dogmatic certainty blinds us to further knowledge.

References

[1] Jurgis Baltrušaitis. Anamorphic Art. Trans. W.J. Strachan (Cambridge: Chadwyck-Healey, 1977), 110.

[2] Ibid., 111.

[3] Ibid., 96.

[4] John North, The Ambassadors’ Secret: Holbein and the World of the Renaissance (London: Phoenix, 2004),175-76.

[5] John North, The Ambassadors’ Secret: Holbein and the World of the Renaissance (London: Phoenix, 2004),175-76.